By Patty G.

For me, Carlos Palacios is a myth. A legend.

I went to Ysleta High School in the mid-1990s, just like Palacios, who everyone called “Chuck” back then. He was two grades ahead of me, and I never had the nerve to talk to him. Even from afar, he stood out; he was just too cool for school. We shared an Algebra II class and I remember watching him do something I never would have dared: he called out our teacher for not doing his job.

“Why don’t you teach us anything?” he demanded — annoyed, but dead serious.

That day, the teacher finally taught us and I was in awe. Not just because it was bold, but because it revealed a kind of integrity I didn’t yet have the courage to imagine.

At the time, I didn’t know it, but that moment summed up who Palacios would become to a generation of El Paso kids: a cultural architect of the city’s punk scene. Palacios himself would never suggest his importance over that of the many kids he learned from and built alongside. But if he loomed large in my imagination, he was even more central to the people who actually knew him.

I’ve dubbed Palacios the “King of the Lower Valley Punks,” a notion that makes his best friend and longtime bandmate Omar Hernandez chuckle.

“He knew everybody and everybody knew Chuck,” Hernandez says, explaining that Palacios was connected to kids from all over El Paso. “No one hated him. You know, a lot of the West Side guys had beef with Lower Valley guys — just stupid shit like that. But Chuck got along with them all. He was just an easy guy to talk to. He likes to laugh and just chum it up.”

That easygoing nature drew Hernandez in. New to Ysleta, Hernandez says Palacios and other punks welcomed him and introduced him to the scene. They’ve been friends ever since — bands, moves and travels together.

“He’s, like, one of the oldest friends I still talk to and regularly hang out with,” Hernandez says. “I’ve been all over the place with the guy; like, traveled pretty much everywhere with the dude, filled up a passport. He’s just a funny dude; he’s always, like, in good moods.”

By the time most of us were worrying about homework, Palacios had already become a fixture of the Lower Valley punk world. His impact was unmistakable: he played in local bands, set up shows and helped other punk kids get a small venue — The Rugburn — off the ground. Tucked away on Alameda, The Rugburn became one of those rare all-ages spaces where kids could hear live music without being turned away at the door.

Nearly three decades later, that fearless kid from Algebra II sits across from me at a coffee shop in South-Central El Paso on a cool October afternoon. As our conversation begins, the atmosphere is marked by his confident cool, tempered by a slightly guarded air: what’s this all about? He’s early for our interview, coffee already ordered. We quickly fall into an easy conversation, and I tell him about our shared Algebra class. “Oh my god, you were at the fucking ‘Mr. Belvidere’ classes? We watched ‘Mr. Belvidere’ everyday. … He would put a bunch of notes on the thing and then we’d copy them. And then he’d put on ‘Mr. Belvidere’ and we would never get to the end of it. We would get like three-quarters of the way through it — there was no resolve.”

Long before he was booking shows, Palacios’ relationship with music began at home, thanks to his older siblings and super-cool parents who allowed house parties. In the 1980s, fraternities and sororities ruled El Paso’s Lower Valley. With them came ragers — kegs, music and DJs working massive setups that blasted punk, new wave, metal, freestyle. In the aftermath of one such party, a very young Carlos Palacios — six or seven years old — stumbled onto something that would change his life.

“There was a crate of records and I started looking through them. I was hella young and I was like, ‘What the hell?’ They were the coolest-looking records I had ever seen. There was, like, Misfits with all sorts of skulls and I was ‘whoa!’ … I was blown away.”

When the DJ returned to retrieve his gear, Palacios’ older brother told him how the younger Palacios thought the records were really cool. The DJ burrowed through those crates and left him with parting gifts: two cassette tapes (one from Misfits and the other from Corrosion of Conformity, which Palacios admits is quite intense for a kid) that he listened to constantly.

“That was the coolest shit ever,” Palacios says. “I was in love with them. I listened to them non-stop.” Recalling one song in particular — Misfits’ “Die, Die My Darling” — he sings the prevalent repeating beep. “Aww, it was just blowing my mind.”

From that point on, music wasn’t just something he liked — it was a way of life. As he grew older, hanging out with kids like Pancho Mendoza, Michael (Mikey) Morales, Ernesto Ybarra and Sergio Mendoza — skateboarding, going to backyard shows, learning how to play bass — he was turned on to the local music scene. This immersion sparked a new ambition. “I just got this harebrained idea,” he laughs. “I was all of 13 — ‘I’m going to start doing shows.’”

With $50 from his mom, Palacios bought stamps and sent letters to every band and label he liked that appeared in Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life, a booking guide for touring bands. The response was more than he imagined and things snowballed.

“I didn’t have a venue. I didn’t own a PA. I didn’t own anything,” he says. “I used to get everybody’s numbers and I would call everybody I knew and ask them if we could have a show at their house on a Monday night, on a Tuesday night, on a random fucking night. I couldn’t do that kind of thing now.”

By 15, he was already years into booking shows. “I was moving up the ranks and I was getting the no-name bands and then all of a sudden Rancid’s calling. I didn’t have a venue, still didn’t have shit. People would ask me for guarantees and I’d be like, ‘Can’t help you with any of that — I’m a kid, I don’t have any money. But, I’ll make sure you have an awesome show.’”

He booked shows wherever he could: people’s houses, gymnasiums, dirt lots across from Ysleta High School, the church down the street, even city Parks and Recreation spaces. Some of those shows have since become punk-scene lore, including one at a rec center where no one showed up to open the space. That didn’t stop Palacios — he and his friends found an outlet on the side of the building and set up the bands. He booked acts like Rancid, Anti-Flag, Total Chaos and Heroin before they broke nationally.

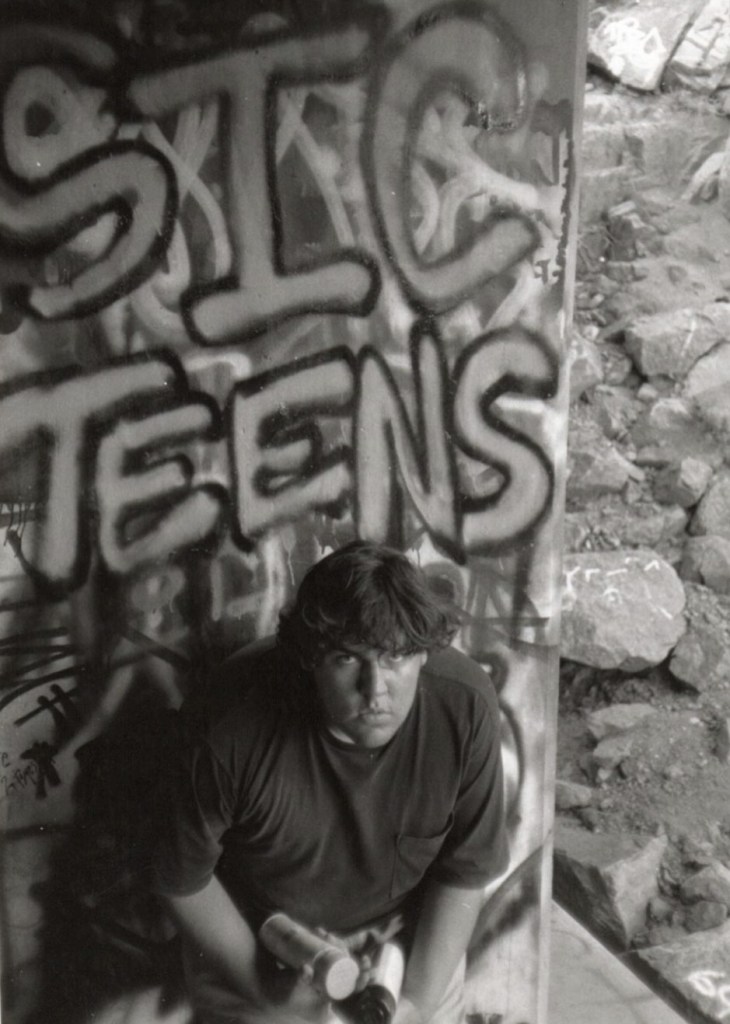

Eventually, it stopped being enough to put other people on stage. Palacios wanted to play (he was a songwriter and frontman too). A couple of bands with best friends followed: Senile, Sicteens, The Slitz. The bands lasted only a few years and they managed a few self-funded tours. “The first tour we did for the Sicteens, we got as far as Deming and the van broke down,” he laughs. “So then my dad had to come meet us. Luckily, my other friend had a van and volunteered to take us on tour.”

Because he had booked so many shows for bands in Berkeley and Oakland, he was determined to attend art school in the Bay Area. This move was pivotal for Palacios: he applied to one school, got in and after graduating in 1996, headed out West. It took him time to find his people, he says, but after a while, he became immersed in the Bay Area music scene.

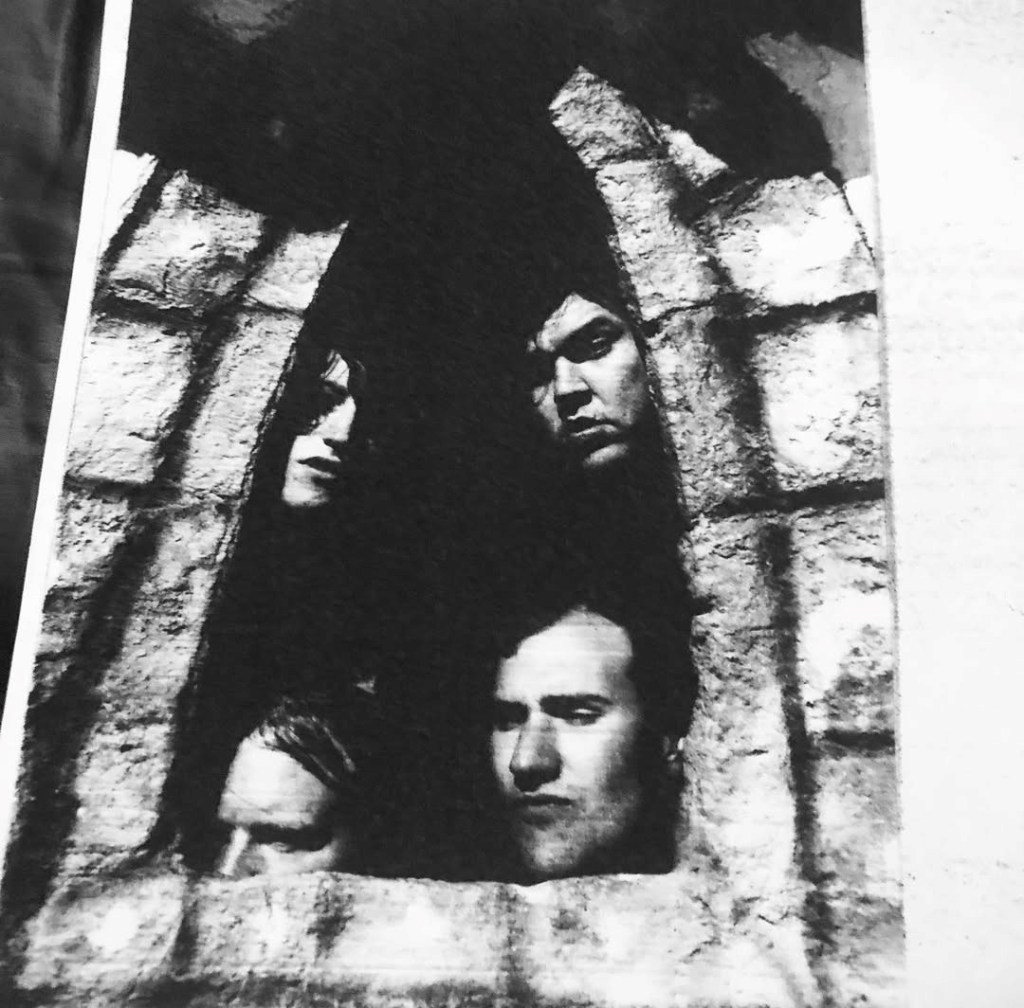

In 1998, along with Bay Area friend Andy Jordan and fellow El Pasoan Eric Johnson, he founded The Cuts, an Oakland psych/garage rock band, with Palacios on guitar, Jordan on bass and Johnson on vocals. The band’s formation and evolution marked a new phase in his music career: they eventually switched instruments because, as Palacios puts it, “(Andy) knew how to shred and I didn’t.” After a trip back to El Paso, though, Johnson left. The band was filled in with kids from Palacios’ school and later with kids in the scene. Soon after, they were getting noticed.

The Cuts signed to Lookout Records after winning a talent contest and toured with The Donnas. These successes represented the high points of that era for Palacios. Still, he describes the tour as ending with a fizzle rather than a bang. “After that, we were kind of done with Lookout,” he says. “But it was alright, because the band was changing.”

The band saw a series of lineup changes and even relocated to El Paso for a while, making it feel less and less like his old band. He reflects on the natural progression of bands: “A lot of times, bands will start one way and they change pretty quickly or soon after or even, their sound is changing, because you, as a band, are better understanding each other,” he says. “Basically, (The Cuts’) music was getting more intense and we couldn’t develop it further” (together).

So Palacios did what he had always done when something stopped making sense — he left the band and started over. This reset signaled a creative shift, this time with Hernandez. Their band, Apache, grew out of that reset. “(Omar and I) started hanging out and writing things together,” Palacios says, explaining that this was happening when he was still in The Cuts. Hernandez one day jokingly filled in for Johnson during a band rehearsal, singing a song called “Ride, Apache, Ride.” When The Cuts performed the song during a show, they called Hernandez up to sing it. “Omar comes up on stage and kind of goes wild,” he says.

A record exec happened to be in the audience and offered to sign them on the spot. “The label guy’s like, ‘I love it, I love it!” remembers Palacios. “He’s like, ‘I’ll sign you guys right now without hearing anything else. If you guys make a band, I’ll put out your record.’ … So we made a band just like that.” The band was able to come full circle and bring drummer Michael Morales, from their Ysleta days, into the fold, and the band’s lineup evolved to include four other members.

Apache was a glam punk band that found real momentum, first in San Francisco and then worldwide. While touring didn’t make Palacios rich, he was having a blast and it gave him something better.

“At one point, when I was in Apache, I was in some coastal Spanish town, it was fucking gorgeous and I was just sitting there thinking the whole time: people work their whole fucking lives to get to where I am right now. And I just got here playing rock and roll?” he says. “I’ve been to so many gorgeous places and I don’t know that I’ll ever get to go back. That rock and roll took me there? I never had a career that made me a ton of money but it got me there.”

But that freedom came without guarantees and it didn’t protect the band from the trappings of the music industry. Issues with their label froze the band’s recorded output and is not currently available.

Apache plans to reunite later this year at The Chamizal in Ciudad Juárez on June 6. Even now, Hernandez admits Palacios is the one still pushing things forward, still making it happen. “You know, I’m a real stick in the mud when it comes to reuniting the band and getting it together,” he says. “So, I was like, alright guys, if we’re gonna do this, I made some rules.” For one thing, their show had to be in Juarez and the second thing was they’d have to have their original guitarist Mark (Ablues), who nobody had seen in years. Turns out Palacios found him and secured a spot in Juarez, so party on.

Palacios has since moved back to El Paso. There’s no grand comeback narrative, no nostalgia play — just motion. He now plays in Krunchies with Wally Byers and Ernesto Carrillo. Their music is a salute to the glam rock that has given them so much over the years. No crazy buzz, just good ol’ rock and roll. Expect an album from them soon with artwork from Juarez artist Malicia Dominguez.

It’s tempting to frame Carlos Palacios as a relic of a specific moment in El Paso punk history. But that misses the point. He was never about permanence or preservation. He was about action: booking the show, starting the band, making something happen when there was no reason to believe it would.

That kid in Algebra II — the one who demanded more — never really left El Paso. He just kept finding new rooms, new stages and new cities where the same question still mattered: Why don’t you teach us anything?

For Your Viewing and Listening Pleasure:

Krunchies Bandcamp: https://krunchies.bandcamp.com/track/good-looking-man

Leave a comment