This interview has been edited for clarity and length. Interview took place in May 2024.

By PattyG

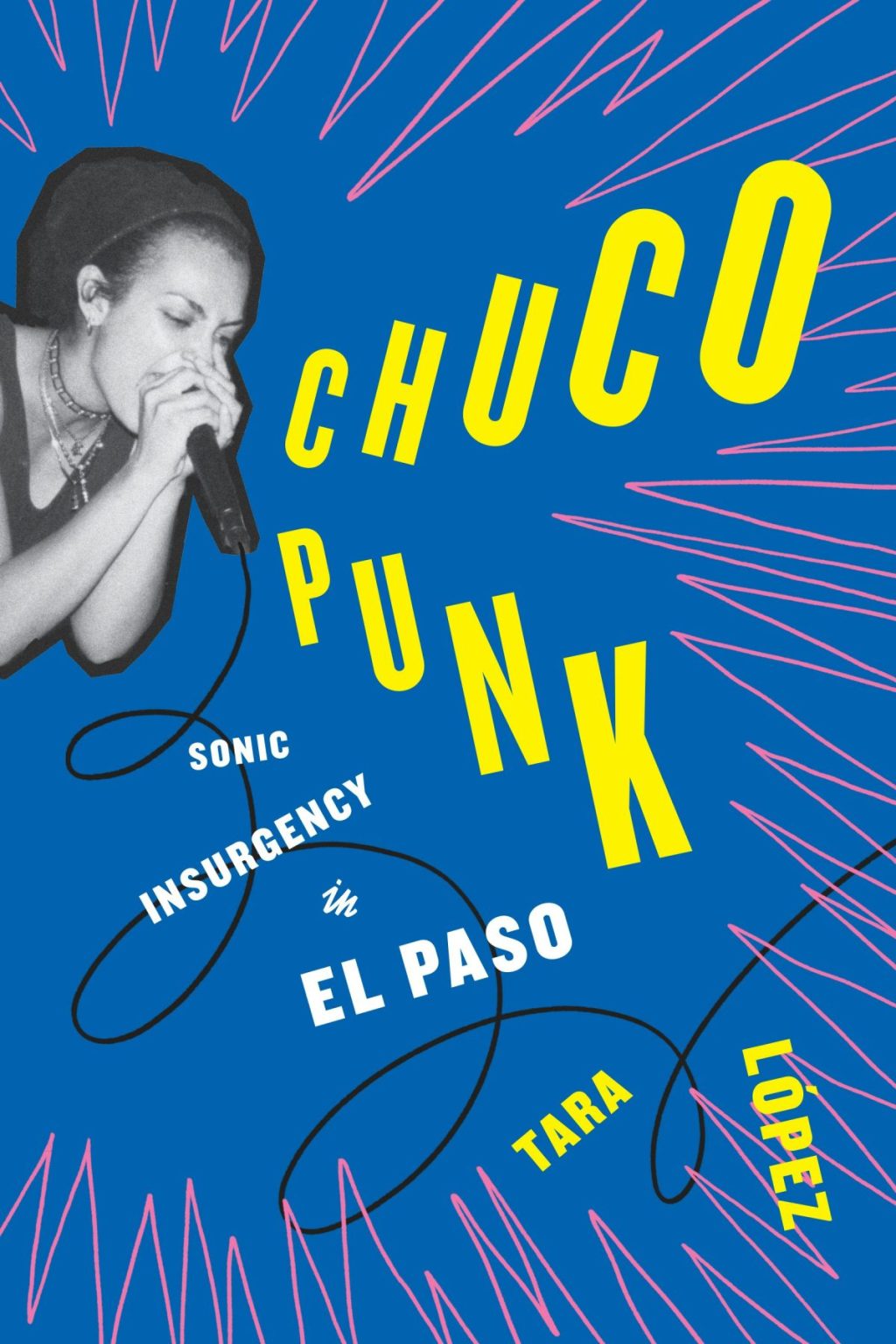

Interviewing more than 50 El Paso punks and collecting El Paso history as far back as the late 1800s, Dr. Tara López has written the seminal punk history of El Paso. The book, published by University of Texas Press, is a quick nostalgic read that offers insight to the social, economic, and political dynamics that inspired El Paso punks. In May 2024, Dr. López took some time to talk to us about what inspired her to write the book, writing a book as an outsider and why she loves El Paso.

PattyG: Well, let’s dive right in; why did you decide to write a book about El Paso’s punk scene?

Tara López: I think the first thing would be because I was born in Dona Ana County, so really the major big city, other than Cruces, was El Paso. My father would often go down there for work and so forth. And then my parents would take me when I was a kid to Western Playland. My parents would just talk about that because El Paso was really the big, big city. But more particularly, as I mentioned in the preface, like for my dad, who was stationed in Roswell, El Paso was the part of Texas where it was not so racist. … So, for my dad and his generation, El Paso was where he could be just himself and not be judged for being a brown man walking around. And I think just even overall, especially with my dad’s side of the family that’s from Northern New Mexico, El Paso is just like New Mexico still. Historically, El Paso was part of New Mexican territory, colonially, and in 1681, it was the capital of New Mexican territory. … There was always this long-standing connection.

But regarding the punk scene, I was in the punk scene in Albuquerque and many of the bands that I knew were from El Paso, like Chinese Love Beads, Better Off Dead. Like those guys were part of the Albuquerque scene, but they were always very clear that they were from El Paso. So, you know, El Paso has always been around in my life since I was born close to there.

My family lived there, and they just had the historic kind of view that a lot of New Mexicans have of your home city, is like “this is nice city.” It’s like we have a crush on you. You’re the cute kid in high school where we’re like, “We love you,” and you don’t even realize it.

But then there’s also the punk elements. So, as I started to do a lot of my own research when I became an academic and looking at movements of people collectively, I oftentimes saw that when there were discussions of punk rock, and especially histories of punk, people of color were oftentimes omitted, and women of color in general, and Chicanas in particular weren’t there, but I knew we were there. Albuquerque was like that and more so in El Paso that there were people of color, so I just knew that that image was wrong, and it was a misrepresentation.

So, I put an announcement on the El Paso Hardcore Facebook group, and I was like, “hey, does anybody want to talk to me – I’m going to write something about El Paso punk.” And the first ones to respond were Mikey Morales and Ernesto (Ybarra) and I just went from there … knowing that it was a special place and that it was a special music culture, and that, people need to know about, that El Paso is a special place and the music that comes out of there is very special.

PattyG: Yeah, absolutely! The thing that’s really cool about the book is there’s that locality of it and there’s something that we can relate to – there are so many people in the book that I know – but more so, I really loved how you tied in all the historical context that people of younger generations from El Paso may not have been aware of.

López: First, I’m glad it reached you and I want everybody to love the book, but people from El Paso, because that was why the book was written, especially Chicanas, especially women, because that’s the position I come from. … Then also the connection with the history is like understanding all of us – and I was learning a lot about El Paso history too – so, for instance, my dad was like, “Do you know that pachucos are from El Paso?” And I was like, “What? I thought they were from Los Angeles.” And he’s like, “Yeah, that’s what I thought too.” So, it’s like a learning process for others too to be like, wow, I didn’t even know that El Paso was that important (to that history). I had a feeling it was and then I would read all this stuff and I was like wow, so much came out of it. But, at the same time, connecting what you all did, it’s not only that people were shaped by NAFTA and shaped by, for instance, when the Klan was in control of the school board in the early 20th century in El Paso, but the communities also shaped what was going on. Like with the (1917) Bath Riots – you have one of the most vulnerable people, Carmelita Torres – you have a woman just crossing the border to work and then she and a whole bunch of women fight back. So, we, as regular people, can push back. … So yes, shaped by the history, but also shaping the history.

For instance, there would be no “Pachuco Boogie” without Don Tosti, whose dad was from Santa Fe. So, when I learned that, I was like, “Oh, there’s another New Mexico connection!” So, I felt a little bit of pride, though he’s all from Chuco. I felt like there’s so much interaction because your city is an entry point. So, way back, some of my ancestors went through it also in the 1700s to get to Northern New Mexico. It’s a passageway for so many people and their ancestors or their families today, so it’s such an important city and you all were a part of making it such an important city.

PattyG: It’s funny that you mention this and, in the book, because I always wondered why we are in El Paso drawn to aggressive stuff? It made sense when I read your book and the history of El Paso, because it’s like, it’s just a reaction to everything, right? The women who participated in the Bath Riots, or people in the region reacting to racism or other injustices, it was a way to be revolutionary. It was really an act of defiance. It all connects.

López: Yeah, I think that the history of a lot of people of color, oftentimes, our parents or grandparents or great grandparents, certainly didn’t have access to education or sometimes the right to vote, but they knew how to make music and they knew how to tell poems or tell cuentos. So sometimes in some cultures, music was the only way that communities had as a form of expression. Sometimes I get from other academics like “oh, you’re writing about music, that’s cute.” First, it’s not cute, but okay. … If you think about the history of African Americans in the South, there were laws preventing them from playing drums. And that was a political push, but it was also a push against culture. So, it makes sense to understand a city like El Paso that’s Hispanic, or Latino, to understand the history of one of the few longstanding ways these people, our people, could express themselves – and that is music because they might not have had political power. They oftentimes didn’t have social power because of racism, but they always can play music, whether it was corridos, whether it’s hip hop or whatever genre people are going to play. Don Tosti was in the symphony in El Paso, but there was still like, you say, a form of defiance. It seemed like “okay, I’m waving a flag,” but you’re literally making noise. And oftentimes people didn’t like that.

PattyG: You did a ton of research – how many people or oral histories did you collect when you were doing this project?

López: So, I talked to 55 people and then there were probably 70 oral histories. So, I could have talked to more, but I wouldn’t have gotten the book done. … Even though there was there was a criticism that there were too many names and people in the book, I think it’s still not enough and hopefully in the future, there’ll be other researchers … and that we’ll be able to go into even more depth.

But I felt like there was this urgent need to make sure to write this book and that the women were included. … They were already there. So, I was like, “I need to make sure that this gets written because oftentimes when music cultures are talked about, you know, queer kids, women, people of color, they’re just on like the little outskirts. I wanted to try to bring in as many of those individuals to the forefront.

PattyG: Was there anything aside from some of the historical stuff that you learned about the El Paso music scene?

López: I think the backyard shows, especially in the Lower Valley, and the role that a lot of women played in throwing those shows in the ’90s. … I just never went to a backyard show when I was in Albuquerque. The landscape is different, and it shows how things are different, rather than impossible, versus Albuquerque. So, I was just so surprised that people could have shows in their backyard and that they have had like big festivals and everything.

PattyG: is there anything else about the book that I didn’t ask you about that you want to mention?

López: I really loved working on this book, and I think maybe sometimes it takes an outsider to shed light on how awesome a city is and El Paso is my favorite city. I am a New Mexican. My favorite state is New Mexico. I will never stop being a New Mexican even though I live in Minnesota. But my favorite city is El Paso and I think sometimes it takes having an outsider to reflect how cool you are, how innovative, how smart people are. And El Paso people are super nice. You have a reputation for being really nice, but it’s also just a very welcoming city. So, I just hope that the book helps others from El Paso realize, if they don’t already, realize how awesome their city is.

Leave a comment