By Patty G.

NOTE: This book review was written when the book was originally published in 2024, it just never got published. But I feel strongly about this book and I still think every El Pasoan should read it. So, below is my late, but still relevant IMO, review.

As a teen growing up in El Paso’s Lower Valley, I longed to be in the Pacific Northwest or on the opposite coast, in the Big Apple, surrounded by exciting people of all types. But more than that, I wanted to be a part of a live music scene that was big and alive. Thinking back on it, I now see how incredibly fucking stupid I was because I was surrounded by a vibrant live music scene in El Paso.

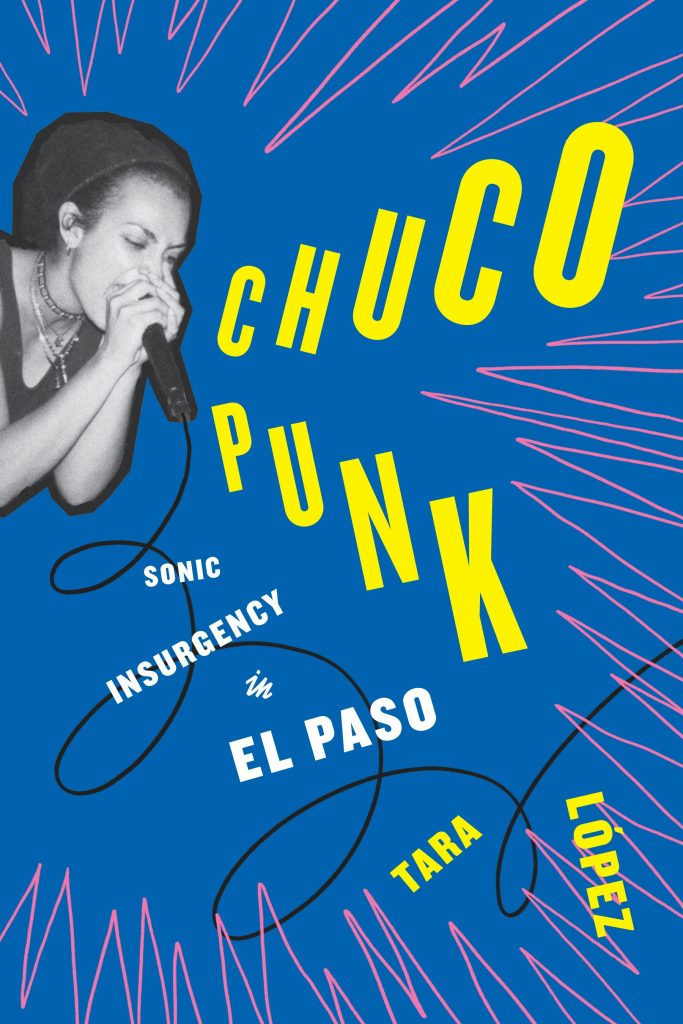

As Tara Lopez puts it in Chuco Punk: Sonic Insurgency in El Paso, El Paso was the “site of cultural resistance that would feed into the reservoir of punk ingenuity by the end of the 1970s.”

In the book, available from University of Texas Press on June 4, 2024, Lopez takes a scholarly, yet passionate, deep dive into how El Pasoans used music as an act of rebellion against systemic racism, poverty and other social injustices. Punk rock, she writes, was the perfect outlet for generations of fronterizos. While punk rock is typically seen as emerging in the 1970s and in cities such as New York City and London, Lopez writes that the seeds for Chuco punk were laid down much earlier in corridos such as “El Contrabando del Paso,” written and recorded during Prohibition, and through pachuquismo celebrated in songs such as Don Tosti’s 1948 masterpiece “Pachuco Boogie.”

“It is telling that both the name of pachuquismo and its central songwriter were from El Paso — from Chuco — revealing the layers of cultural resistance that predated Chuco punx and even Don Tosti,” she writes.

Lopez, who grew up in Dona Ana, N.M., and later in Albuquerque, shows a reverence for El Paso, a town not far from her own. She notes that El Paso has always been that scrappy little West Texas town that could (my words, not hers). But what really stands out to her is the perseverance of its people, something exemplified in its music. Its music scene is a direct reflection of the political, economic, and social challenges faced by fronterizos; but more important, its music scene is a direct reflection of how chingon fronterizos are and have been throughout our history. El Paso is often portrayed as a dusty old Western town devoid of culture or talent or anything worth paying attention to, but in Chuco Punk, El Paso is the backdrop to a musical revolution and is just as important to the punk rock narrative as is New York City’s or DC’s punk scene. “Instead of taking for granted that places exist statically in space, historian Monica Perales in her research of El Paso’s Smeltertown argues that people are active in re-creating space to create meaning and community. Punx in El Paso did the same,” Lopez writes.

Instead of taking for granted that places exist statically in space, historian Monica Perales in her research of El Paso’s Smeltertown argues that people are active in re-creating space to create meaning and community. Punx in El Paso did the same.

The first wave of Chuco punk came in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when El Pasoan Tito Larriva arrived in Los Angeles and started The Plugz, singing songs with Spanish lyrics and ushering in a flood of Chicano punk bands that led LA’s emerging punk scene. The Plugz’s success had a ripple effect on Chuco punks. They not only started punk bands and a music scene for others who didn’t fit in and for those who had something to say about the changing political, social, and cultural landscape that NAFTA and an increasing Border Patrol presence brought to El Paso. Chuco punks such as Bobbie Welch increasingly used their rasquachismo attitude to book shows, sometimes in dry riverbeds (allowing for international shows!) and garages.

The second wave of punk arrived in the 1990s, with Chuco punks as tenacious as their forefathers, but this time with a greater participation from female and queer punks than before. Lopez interviewed dozens of Chuco punks for the book and I want to mention them all — many of them are my friends from the Lower Valley or simply mythical figures I sheepishly admired as a nerdy teen — but I don’t want to spoil any surprises.

Lopez’s Chuco Punk is a love letter to the city’s sonic history and the kids that endured despite the many challenges they faced. Lopez shows such respect and admiration for the El Paso and Juarez community and the perseverance of its people that I shed a few tears at moments, reminded of the privilege it is to have grown up here and to be able to raise my own kid with the presence of la frontera in our daily lives and what a unique and empowering experience that is.

Chuco Punk gives a voice to many in the El Paso music scene, telling the story of how a scrappy little town and its people can create musical beauty and change despite so many social, political and geographical challenges.

Leave a comment